DeRudio himself recalled the events of that fateful day some twenty-three years later in an interview with the New York Times published on March 20, 1881. In it, he related that while he was being led up the stairs to the guillotine after Pieri had been executed, on March 13, 1858, he was intercepted by a gentleman on a horse, who informed him and his guards that no warrant for his execution had been received and he was to be returned to his cell. In his own words DeRudio recounted, “That night I became acquainted with the fact that the Empress Eugénie had suspended my execution until she could talk to the Emperor. My wife had presented her with a petition signed by many members of the highest English nobility, and received the promise that my life should be spared for the sake of my family. Two days later, March 15, the birthday of the Prince Imperial, I was taken to the Palais de Justice and re-sentenced to imprisonment for life at Cayenne.” DeRudio for the second time in his life had escaped a death sentence.

The next day the court sentenced him to hard labor for life at the notorious Devil’s Island prison in French Guyana. A reprieve from a death sentence in exchange for one of hard labor for life was certainly no consolation. Life in the penal colony was so brutal and harsh, that French writer Victor Hugo once described it, as “the dry guillotine” since chances of surviving there were tantamount to a death sentence. DeRudio, however, managed to successfully escape from prison on his second attempt in 1860 after two-years of confinement. Fleeing with a group of 12 fellow convicts in a stolen boat, they confronted an even more formidable challenge: that of surviving a 1,000-mile sea voyage in an unequipped, crowded, small boat.

Sailing across the open sea they eventually reached British Guyana where they were granted political asylum. DeRudio soon after departed for England, arriving in London in February of 1860 and was reunited with his family once again. While in London he met with Giuseppe Mazzini who put him in contact with Italian sympathizers. They in turn arranged for, and financially supported, his flight to America so he could escape outstanding arrest warrants that had been issued for him on the continent. His family would follow him later once he had become established in his adopted homeland.

"Italian Forrest Gump"

Major Charles C. DeRudio

DeRudio Family

Coat of Arms

Giuseppe Garibaldi

Ne perdez pas votre tête

Civil War in America

Arriving in New York in 1864, he found the country in the middle of the Civil War. DeRudio, who was an ardent abolitionist, applied for a commission as an officer in the Union Army but was turned down. He then went to work cultivating contacts with influential people who would support his enlistment, but ultimately realized that his only option was to accept a substitute enlistment from someone willing to pay him to take their place. This he did and in return was paid around $1,000 allowing him to send for his wife and children in England to join him. He entered the army as a private in the 79th Highlanders New York Volunteers Regiment. Because of his repeated acts of bravery during the Siege of Petersburg, Virginia, he felt that a commission would await him if he could transfer out of the 79th Highlanders and into the Colored Troops where his chances for advancement would be much better. He applied for and was granted a transfer and then was commissioned by General U. S. Grant to Second Lieutenant in the newly formed Company D, 2nd US Colored Troops Infantry (USCT) where he led African-American troops until the end of the war. In February 1866 he was honorably mustered out of the Army when the war ended.

A studio photograph taken in 1864 of Black Union soldiers with a white officer and later used to create a color-lithograph recruiting poster.

The Battle of The Little Bighorn

In 1867 DeRudio requested a commission in the regular Army and was turned down when he failed a required physical and the War Department learned of his assassination attempt in France. He visited a second doctor who passed him as physically fit to serve and then enlisted Horace Greely, the famous newspaper reporter, who knew of DeRudio’s ardent anti-slavery stance, in his cause. Because of Greely’s efforts and others, he gained an appointment as a 1st Lt. in the famed US 7th Cavalry in July of 1869. It is known that the 7th Cavalry Commander, General Custer, thought little of his new 1st Lt., considering him an inferior candidate due to his revolutionary activities in Europe.

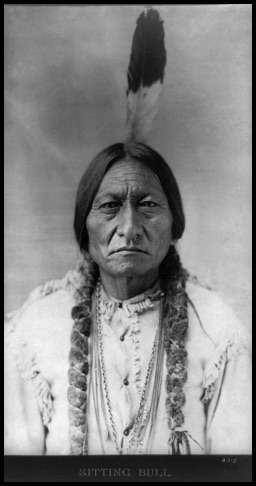

Seven years later when General Custer led his troops into the ill-fated Battle of The Little Bighorn in June of 1876, 1st Lt. DeRudio was the oldest serving U.S. Army officer among the 7th Cavalry. During the battle, DeRudio was under the command of Major Reno whose poor leadership and hasty retreat caused him and several others to become separated from the main body of their troops. DeRudio became trapped among the trees and brush after his horse was shot out from under him and along with another soldier hid out for thirty-six hours while periodically fighting and hiding for their very survival while surrounded by enraged Sioux warriors. After the battle in 1878 DeRudio testified before the Reno Court of Inquiry. In 1882 he was promoted to Captain and assigned to Fort Yates on the Standing Rock Reservation, North Dakota, where he met Hunkpapa Lakota chief, Sitting Bull.

Photograph by D. F. Barry, 1885

Library of Congress

“Old Rudy” as he was affectionately known by his comrades-in-arms, retired from the military in 1896 and moved his family to San Diego. Then in 1898 the family moved to Los Angeles where in 1904 he received the rank of Major U.S. Army Retired. Early on the morning of November 1, 1910 he died at his home on New England Avenue of advanced age and various other complications. A private funeral was held at the home with only the immediate family and a few close friends in attendance.

His body was cremated and, according to his wishes, his ashes were mixed with soil from a white rose bush, symbolic of the three white roses that are part of the di Rudio family crest. His wife and children accompanied his ashes from Southern California to the National Cemetery in San Francisco for burial. He and Elizabeth (Eliza), his faithful wife of fifty-five years who stood by him throughout his various exploits, are both buried in the same unremarkable plot overlooking the Golden Gate. For a man who had been born into such noble surroundings and whose life had been guided by fate through incredible journeys for so very long, this was a modest ending. One goal that he was never able to attain, however, was being allowed by the Italian government to return to the very nation he had sacrificed his youth to help establish.

In Mark Twain’s book Following the Equator, Part 2, a maxim attributed to Pudd’nhead Wilson’s calendar could have been written to describe the life and times of Major DeRudio. “Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn't”.

100th Anniversary Memorial Observation

November 1, 2010

Grave of Major Charles C. and Mrs. DeRudio

Grave decorated for the 100th anniversary of Maj. DeRudio’s death

U.S. Army Cavalry kepi and three white roses symbolic of the

DeRudio family Coat of Arms

Italian Consul General Fabrizio Marcelli, Roberto Bonzio and Cesare Marino

Grave with the flag of Belluno

The memorial was concluded with David Hardiman playing Taps

The Life and Times of the “Italian Forrest Gump”

One thing Italian-American U.S. Army Major Charles C. DeRudio can never be accused of is having an ordinary life. Major DeRudio, sometimes called the “Italian Forrest Gump,” due to his life long incredible experiences and exploits, makes a Hollywood action movie pale in comparison.

Major DeRudio was born Count Carlo Camillo di Rudio in Belluno, Italy on August 26, 1832, the son of Count Ercole di Rudio and Countess Elisabetta de Domini. Italy, at the time, was under French, Austrian and Papal occupation. In 1845 at the age of 13 the young Count entered the Austrian Military academy of St. Luca in Milan with his older brother Count Achille. By the age of 15 during the uprising of Milan in 1848 he and Achille left the academy with the Austrian Army during their withdrawal from the city and while marching north became disgusted while watching a series of atrocities committed by soldiers against innocent civilians. When a commission was offered them they refused and, for their refusal, they were sent to Austria and jailed. Their family appealed for their release and finally a conditional release was granted, but only if they returned home. Instead, the two bothers went to Venice and enlisted in Colonel Fortunato Calvi's resistance movement for Italian liberation. A short time later Achille died, either from wounds sustained during the earlier battle at the military academy in Milan, or from those suffered in defending Venice. DeRudio's role at Milan and in Venice were the first events that started a life long series of unimaginable adventures.

Rome

After leaving Venice he joined Garibaldi’s Redshirts in Rome and fought against the French Army where he was captured when a bolt of lightening lit up his red shirt revealing him to the enemy. While being held in prison, he killed a guard in a failed escape attempt and was spared a death sentence due to his young age, and then sentenced to prison. He eluded the sentence by escaping while on a forced march of prisoners to Civita Vecchia. He soon found himself in Genoa from where he took a ship to America but fate intervened when the ship put into port during a savage storm. He took this unexpected turn of events to be an indication that he should return to Italy and continue in his quest for unification. But while in Marseilles on his way back, he was arrested and ordered deported to England. Before he could be sent there he escaped and went to Paris. After leaving Paris and while trying to return toItaly he was arrested by the Swiss police and spent several months in jail before being offered an opportunity to be deported to England or the U.S. He chose England.

Arriving in England he worked on the docks and eventually married, started a family and became part of a plot with Felice Orsini, Giuseppi Pieri and Antonio Gomez, to assassinate Napoleon III, Emperor of France, in hopes of removing him as an obstacle to Italian unification. The unsuccessful assassination attempt was made on January 14, 1858 when the four conspirators threw three bombs at the Emperors royal carriage when it arrived at the Paris Opera House. The attempt ended with eight people being killed and 142 wounded, while the Emperor and his wife remained unharmed and became even more popular because they had some how miraculously survived. Shortly afterward, DeRudio was arrested along with his three co-conspirators. Their trial took place on February 25, 1858, lasted only two days, and ended with all four being found guilty. They following day DeRudio, Orsini and Pieri were sentenced to death while Antonio Gomez was given “hard labor for life” due to “extenuating circumstances” and in no small part to his having cooperated with authorities.

However, on March 12th DeRudio’s death sentence was commuted to life at hard labor. The reprieve was granted based in part on his having asked the court for clemency and the efforts of his wife’s petition along with pressure from the English Ambassador in Paris who requested a commutation.