Even in ruins, Wickham Stone Park maintains its unique character

of Henry’s leg and the upper bodies of the two Kennedy’s minus heads and arms, all destroyed by vandals and time. The remnants of Kefauver’s shoes reminded me of an ancient vandalized Roman sculpture in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art that shows only a portion of a foot.

Originally, below the portrait of Patrick Henry, was the cement Liberty Bell that has been removed to the Oak Ridge location. Driving to Palmyra near the Kentucky border in northwest Tennessee, I couldn’t help but think of the ancient city of Palmyra located in today’s Syria and once ruled by Queen Zenobia. After taking Egypt from the Romans and having lost a later war, “The Warrior Queen” was captured by Emperor Aurelian who transported her to Rome where she was paraded through the city bound by golden chains. Nobody knows what eventually became of Queen Zenobia after her arrival, so the mystery of her fate survives to this day.

Arriving at Wickham Stone Park located on rural Buck Smith Road just outside the small town of Palmyra, you are greeted by the remnants of a once powerful and personal place that has managed to survive much like its ancient namesake, in spite of the effects of weather, neglect and vandalism. E. T. Wickham (1883-1970) the park’s creator was a tobacco farmer who, upon retirement in 1950 at age 67, set about on a twenty-year artistic endeavor creating the many people and events that he honored and wanted to memorialize in his roadside environmental concrete park. Wickham moved from the family home in Wickham Hollow near the cemetery to a new log cabin home he constructed on Buck Smith Road so he and his wife could be close to his planned park. Those who knew him believe that he was always an artist and that his newly found freedom of being retired finally allowed him the time to begin his labor of love. Eventually he would use over forty tons of cement that he sculpt directly over metal armatures and cast to create his sculptures. By the time of his death the park had more than forty larger than life size statues, several of which are mounted on massive cast cement bases. Wickham’s earliest work can be traced to a carved headstone he created for his son, Ernest, who was killed in France during WWII. Eventually he would carve headstones for both his and his wife’s graves located in the family cemetery.

Wickham found inspiration for his art by depicting native-Americans, famous Tennesseans and other famous Americans, along with family members and religious motifs based on his Catholic faith. The original Stone Park as he created it can be divided into two distinct areas along rural Buck Smith Road. Blended in with this mix are monuments to three wars and war heroes. The area in the vicinity of his log cabin on the south side of the road was where his earliest pieces for the park were created, including the, Blessed Virgin Mary with Snake (early 1950s) along with his large sundial said to be accurate within two minutes. On the opposite side of the road were twenty-one of his monumental non-religious sculptures. Eventually he built the modest United Sportsman’s Club in the middle of his park, so that locals would have a social place to meet with Wickham, sponsoring turkey shoots and other activities for a number of years. After his death the area became a Lovers Lane with kids drawn there at night because of the spooky nature of the life size

Today, only five of the original twenty-one roadside pieces remain in situ. In 2003, grandson Tony Evans selected a second site to relocate some of the pieces in an effort to prevent further damage, removing all but the largest and heaviest from the original park setting. The five remaining pieces on Buck Smith Road are still there due to their size and weight that precluded their being moved to the more secure site along Oak Ridge Road about a mile distant.

This new site is at the home of Wickham’s daughter, Mary Wickham-Evans. The site was chosen so that they could be monitored in an effort to prevent further vandalism. Here, on the high ridge protected behind a wire fence along the edge of the road, are ten sculptures in various states of disrepair. Evans plans to move five more remaining pieces at the original site along with the cabin next year. His future plans call for an open invitation to artists to come to the park and help in the restoration of the pieces. Evans also told me of his plans to carve a limestone sign with the Wickham Stone Park name on it as part of the tableau he is creating at the Oak Ridge Road site.

The remaining original pieces on the manicured north side of the original park site offer a teasing glimpse of what it once was. Even in ruins however, these pieces provide powerful testimony to their creator and evoke in the viewer a reference to ancient sculpture. Due to their deteriorated condition with many of the interior armatures exposed, you can see the materials Wickham selected to reinforce his work and gain an intimate sense of his construction skills and techniques. Collectively, the armatures represent an eclectic group of pipes, wire, metal screen, bolts and other odd bits and pieces of metal that he acquired to add strength and rigidity to the works. It is here, too, now hidden among a small grove of pine trees, that Wickham portrayed himself in Rider and Bull (1961). In it he is shown riding a bull while holding its tail in one hand and throwing a lasso with the other. Remnants of the sculptures nighttime illumination with red light bulbs are to be found in the bull’s eye sockets and in its rear end, a humorous touch by the artist. On the front of the pyramid-shaped base is the message “Do Not Touch or Swing on Statues.” While on the base he inscribed “Headed to the wild and Woley (sic) West, Remember me Boys While I am Gone.” Today a few patches of the original color accompany the headless bull-rider, along with spray painted graffiti, corroded electrical sockets and evidence of the original armature of the horn. But Wickham’s memory and humor live on in spite of the piece’s deteriorated condition.

Just beyond Rider and Bull are four other sculptures including his depiction of Andrew Jackson (1961), reminiscent of the statue of Jackson on the capitol grounds in Nashville that he once visited and measured for his sculpture. It should be noted that due to Wickham’s great engineering skills Jackson’s horse rearing up remains quite solid and shows little sign of any damage. Next to it is WWII Memorial (1959) whose soldier was modeled using a photo of his son Ernest, killed during WWII in 1944. This powerful piece pays homage through various inscriptions on its base to the sacrifice of all soldiers who go to war. The headless soldier standing at attention still rests his right hand on a large artillery shell while his left arm is now missing. This is followed by a tableau portraying three distinguished Americans titled Estes Kefauver, Patrick Henry, J. F. Kennedy and the Liberty Bell (1963). Wickham later added Robert Kennedy in 1969. Today, sadly all that remains are Kefauver’s and Henry’s shoes with part

statues along the darkened road. With the park being so accessible it was soon vandalized by people shooting at the statues and driving their trucks into the bases of the pieces destroying many of them.

The final sculpture at the site is of two oxen from, Team of Oxen and Covered Wagon (1965). While the covered wagon is long gone, the oxen remain permanently connected by their substantial concrete base and yoke. It is interesting to note that Wickham used an oxen team to go into town in an era when most people rode horses thus setting him out among the crowd and retaining his pioneer spirit. The sculpture originally had his teams wooden yoke that later was replaced with the more permanent cement version.

On the opposite side of the road are several remaining works in an overgrown and jumbled area too dense to penetrate or see. It was on this side of the road where Wickham constructed his log cabin home and erected his many religious themed pieces including his first, that of the Virgin Mary. I was told later by his grandson, Kenny Evans, that, “… no one has been down in that area for several years” and that the status of the sculptures there was unknown. This is the area that future plans call for the removal of five remaining pieces.

At the new location, as mentioned earlier, along Oak Ridge Road with its dramatic backdrop and lacking the surrounding growth of the original site, you can fully see and appreciate the amount of damage the sculptures have suffered over the years. These remaining fragments are evocative of ancient classic sculpture and have taken on a mystique all of there own. One piece in particular titled, John Wickham on Horseback and plaque with Bull’s Head (1960) is reminiscent of a Tang Dynasty horse and rider. This is a classic tableau with Wickham’s brother, Dr. John Wickham, depicted sitting on his prized now headless horse while the old doc is both headless and armless. The accompanying Bull’s Head Plaque depicts a Texas Longhorn steer with one horn, above a memorial plaque listing the names of local doctors including his brother, who was tragically killed in 1915 after having been shot during a dispute.

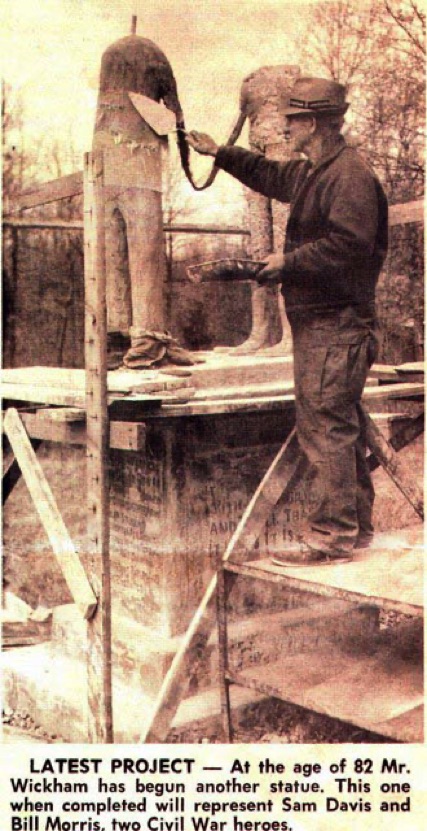

Another powerful piece located here is that of Sam Davis and Bill Marsh (1966-1967) shaking hands. Confederate hero Sam Davis, a young soldier executed as a spy in 1863, on the left and Bill Marsh, Wickham’s maternal grandfather who was one of only two people in the county to vote against secession, on the right. While the sculpture is in terrible repair, their hands are forever joined in forgiveness through the exposed iron armature, thus confirming the message of reconciliation on the base that reads, “It Is All Over With - Now - Bill And Well That It Is As It Is.” While working on this piece one day in the 1960s he wrote Wickham Stone Park on a board thus naming the creation for the first time. A newspaper photograph taken at the time of construction with the then 82-year-old Wickham applying cement, ironically shows the statute in an almost identical condition. Another family photograph shows the completed statue with Wickham, his daughter and his grandson proudly posing in front of the newly completed piece.

While it is sad to see the remnants of this once vibrant and colorful park in such disrepair, Wickham’s powerful legacy lives on in the sculptures’ evolving transformed state. They now tease us with their faded and broken images much like the Winged Victory of Samothrace does to viewers in the Louvre, who must imagine how it once looked by creating mental images of the missing pieces. These new configurations brought on by neglect, weather, vandalism and indifference can now only be viewed for what they were by going through old photographs and home movies. Yet in their present condition they leave the contemporary viewer with powerful imagery that has taken much time to achieve. Offering proof of the old adage that the test of great art is being able to transcend the effects of time.

When Wickham died in 1970, he willed that his land be divided among his children and that the park go to the Catholic Church who, after a few years, resold the property to the family due to its lack of interest and the costs involved in maintaining the sculptures. Fortunately this repurchase has instilled in his surviving family a pride of his achievements along with great motivation to preserve and protect the art works for future generations.

Unfortunately, many Folk Art sites have suffered a similar fate once their creators die. The challenges presented for preservation are often formidable due to the unique manner in which they are created and the associated costs to maintain and preserve them. The tasks of caring for these highly personal places can be overwhelming as well. Folk Art by its vary nature is a uniquely manifest vision of its creator and so personal and eccentric in its context that it causes a vast majority of people to never fully appreciated their artistic or aesthetic value. Without their creators’ love, daily work and maintenance these outdoor sites soon yield to the forces that affect them. Sometimes, at best, only an arrested state of decay can be maintained before they fade into oblivion.

E.T. Wickham and his wife, Annie, are buried in the Wickham Family Cemetery along with their son, Ernest, with the headstones E.T. carved along with his cement Angel (1952) created for Ernest’s grave. Unlike many of his pieces, the Angel sculpture is in excellent condition with family members involved in its ongoing maintenance and preservation. The angel displays its humorous side by the use of nails along the wings and back to discourage birds from landing on it. It reminded me of the giant WREN bird sculpture, the former mascot of Alf Landon’s local radio station in Topeka, that is now in Huntoon Park which is also covered with nails.

So, much like the ancient city of Palmyra in the Syrian Desert that today offers viewers only a fleeting glimpse of its once vibrant life, Wickham Stone Park, too, only offers its viewers a partial look of what it once was. Anyone traveling within a hundred miles of Wickham Stone Park should take a detour to see these wonderful examples of folk art and enjoy a part of our unique American heritage. It will be a trip well worth the effort and one always to be remembered.

Other Wickham sculptures that have been removed from the site can be found at various locations throughout the state. These include the sculpture of Tennessean and WWI hero Sergeant Alvin C. York (1961) and the Sleeping Dogs (1952) in the Trahen Art and Theater building at the Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, Tennessee. Several small pieces of his art and fragments of others are located at the Customs House Museum also in Clarksville. And one of his better know works titled, Ft Campbell Soldier (1968) a sculpture for which he was commissioned is located in front of the Soldier’s Chapel, at Ft Campbell, Kentucky. His work was also displayed at the Folklife Festival during the 1982 World’s Fair in Knoxville, Tennessee.

A show of E. T. Wickham’s work titled, E.T. Wickham A Dream Unguarded took place in 2001 at the Custom House Museum and Culture Center, Clarksville, Tennessee. An exhibition catalog titled, A Dream Unguarded, is available for purchase—the cost is $25 including shipping. To purchase a copy, contact the Custom House Museum at

(931) 648-5780.

An excellent web site on Wickham Stone Park can be found at:

Patrick Henry, John Kennedy and Robert Kennedy

Andrew Jackson, Nashville State Capitol grounds

WWII Monument and Andrew Jackson

Senator Esyes Kefauver & Patrick Henry's Feet

Roman Foot on Base

Liberty Bell with painted crack,

Nashville State Capitol grounds

Liberty Bell from tableau at Oak Ridge site

E.T. with completed statue of his brother

Doc. Wickham

Photo courtesy of the Wickham family

Liberty Bell from tableau at Oak Ridge site

Bull's Head Plaque at Oak Ridge Road site

Davis-March statue with E.T., daughter Mary Wickham-Evans and grandson Kenny Evans

Photo courtesy of the Wickham family

Davis-March statue on Oak Ridge Roady

Newspaper clipping courtesy of the Wickham family

Wife Annie Wickham's headstone in Wickham Family Cemetery

E.T. Wickham's headstone in

Wickham Family Cemetery

Cemetery Angel in

Wickham Family Cemetery

WREN sculpture in

Huntoon Park, Topeka, Kansas

Native American chiefs, Piomingo and Sitting Bull

at Oak Ridge Road site

Roman leg fragments

Photo by author courtesy,

Metropolitan Museum, New York

Anthony Peay, three-term Governor

of Tennessee

at Oak Ridge Road site

Roman sculpture

Photo by author courtesy,

Metropolitan Museum, New York

Statues of Montgomery County Farm Agent

Lester Solomon and Daniel Boone at

Oak Ridge Road site

Andrew Jackson and WWII Monument

Self portrait of E.T. Wickham riding a bull

Buck Smith Road, Oxen

Oak Ridge Road